THE HIVE MAY 2025

Punta Chivato

As I promised last time, this month I am going to cover the Botany/Geology walk that I co-lead in March with Warren, a geologist who lives part of the year in Punta Chivato.

Punta Chivato (PC) is located about 45-60 minutes north of Mulege. To get there, it's about 15 minutes from Mulegé to the turn off at Palo Verde (unless you get stuck behind some trucks or slow poke cars on the twisty, potholed grade out of town). From the junction, after you drive down the three blocks of paved road, you hit dirt for the next 16 km. It can be rough going in parts and depending on your vehicle, comfort level and final destination at PC, it can take another 15-45 minutes. We were to meet up at El Hotelito (a small hotel and restaurant not too far from the airstrip) so it took me a comfortable, unrushed 45 minutes total to get there.

A number of years ago, Warren and I collaborated on a similar walk and we had such a great time with a small group of ex-pats from the area. This was his farewell tour and I think almost everyone who lives out in the isolated community must have shown up.

The map below shows each of the four stops on the tour and are numbered in the order described below.

Geology Notes.

I certainly learned a lot about the formation of Punta Chivato, which is a promontory with four smaller points. The area is part of a volcanic complex known as the Comondu Formation, named after the two small towns of San Miguel de Comondú and San Jose de Comondú–approximately 72 mi (116 km) almost due south of PC–which appear to be the epicenter of a gigantic volcanic field that reaches its maximum depth of about 13,000 feet around these towns and gets shallower radiating out and away.

The oldest volcanic rocks (lava) known to have originated locally in PC are from an eruption that occurred approximately 15 mya. These can be seen in the following set of images taken on the camping beach located between Punta Cacarizo andt Punta Cerrotito (see #1 on map).

In a volcanic eruption, ash particles are ejected in what is known as a pyroclastic flow that can travel at 4-5 times the speed of sound, covering the landscape in thick layers of ash. As the volcanic eruption continues, progressively larger pieces of magma (ejecta) spew from the volcano. The texture and makeup of the ash and lava that eventually comes to rest depends on the gases present at the time. In the images of the ash flow below (some from this tour and some taken in 2023), it is possible to see how different types of chemicals affected the color of the ash and how some of the molten lava and gases formed shards of glass within the layers of ash as it cooled rapidly, giving those layers a gritty texture. Volcanic cinders, larger chunks of lava, are strewn far and wide on the promontory and the general region.

This pyroclastic flow is located by the camping beach (see #1 on map). It extends approx. 50 meters, including a section beyond what is visible here higher up within the outcrop at far right.

The dark greenish-black rock is a lava flow (basalt with some olivine) that lies on top of the pyroclastic (ash) flow. There is an offset in the darker material to left and right that represents a fault.

Looking south along the flow. The presence of sulphur colors the yellowish ash.

Looking NW from the lava flow. The reddish lower layer of ash is from the presence of iron when it was formed.

Bottom to top: fine yellow (sulphur); fine gray; fine red (iron oxide); speckled, rough white (minute glass shards); reddish with 2-4 mm D particles (iron oxide).

Closeup of the upper few layers with the gray glass-containing layer & coarser reddish layer. Above those is a coarse gray layer then a layer of small lava rocks.

Another look at the upper layers. Grayish beach sand in this and upper images obscures some of the layers.

A closer look at the lower layers. Gray beach sand can be seen between & around the ash.

Another exposed section of the ash flow at the base of the hillside about 50 m to the south of the first flow site

The flow disappears briefly then pops out again, still along the base of the hillside only 15-25 m to the south of the previous site.

Our next stop (#2 on map) on the tour was Playa la Palmita and the bluffs located near the airstrip and houses. The rock shelf (at right) and bluffs are composed of sedimentary arenaceous mudstone. The area used to be part of the sea floor and represents the second oldest rock known to have formed locally, somewhere between 5 and 3.5 mya. Dating is possible because they contain the fossils of sand dollars in the genus Scutella that became extinct after 3.5 mya. We learned that because clay particles are so fine, they are last to settle out of water and that it will only settle to the ocean floor in relatively deep water, away from the wave action occuring near shore. It is not known how deep the ocean was when these bluffs were formed. But from studies of the area, the sea level appears to have been around 200 ft higher in the distant past, explaining the limestone bluffs farther inland that rise to about that elevation (stop #4).

Our next stop (#2 on map) on the tour was Playa la Palmita and the bluffs located near the airstrip and houses. The rock shelf (at right) and bluffs are composed of sedimentary arenaceous mudstone. The area used to be part of the sea floor and represents the second oldest rock known to have formed locally, somewhere between 5 and 3.5 mya. Dating is possible because they contain the fossils of sand dollars in the genus Scutella that became extinct after 3.5 mya. We learned that because clay particles are so fine, they are last to settle out of water and that it will only settle to the ocean floor in relatively deep water, away from the wave action occuring near shore. It is not known how deep the ocean was when these bluffs were formed. But from studies of the area, the sea level appears to have been around 200 ft higher in the distant past, explaining the limestone bluffs farther inland that rise to about that elevation (stop #4).

Mudstone shelf and bluffs on the east end of "Shell Beach".

Fossilized sand dollar in the genus Scutella within the mudstone bluff.

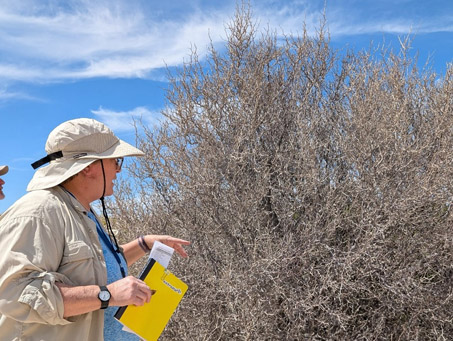

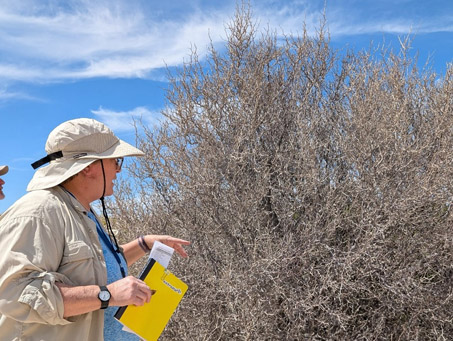

Our third stop of the day was not very far west from the previous one, but because of some deep ravines between the two and the lack of a direct road, the drive took about 15 minutes. After all the cars had arrived and parked, we all gathered around so I could talk briefly about the plant communities at PC as well as about what we were seeing right where we were standing...which was on an ancient seabed that had secondary gypsum deposits, embuing it with a pale gray color, and that was home to what was currently a lot of very gray, mostly leafless plants.

Our third stop of the day was not very far west from the previous one, but because of some deep ravines between the two and the lack of a direct road, the drive took about 15 minutes. After all the cars had arrived and parked, we all gathered around so I could talk briefly about the plant communities at PC as well as about what we were seeing right where we were standing...which was on an ancient seabed that had secondary gypsum deposits, embuing it with a pale gray color, and that was home to what was currently a lot of very gray, mostly leafless plants.

Warren then went on to describe how this area, extending as it does inland from the beach for about 300 to 400 meters, was formed by the constant ebb and flow of the tide over millenia. The secondary gypsum deposits arrived much later, most likely on the wind and tide from Isla San Marco, located not far offshore north of PC.

With plant lists in hand, we then headed down from the bluff to the beach and over to a shallow arroyo extending from the beach dunes back up into the marine terrace. Along the way I stopped to talk about some of the adaptations of the dune plants we were seeing, mainly: Sonoran Saltbush (Atriplex barclayana var. barclayana), Iodinebush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), Alkali Heliotrope (Helioptropium currasavicum var. oculatum), and Dyebush (Psorothamnus emoryi var. emoryi).

Discussing a Red Elephant Trees (Bursera hindsiana) found in the nearby arroyo & how the low, contorted, horizontal branches & dense branchlets on the lee side shows the pruning influence of the wind.

Unlike the previous tree from the (wind tunnel) arroyo near the beach, this Red Elephant Tree is c. 250 m from the coast. While it is also only about 2 m H, it has more vertical, open branching.

Just a bunch of dead sticks, right? Nope. This is the cactus Dahlia-root Cereus, (Peniocereus striatus). It is growing in the open, but they are more likely to be well hidden within, and supported by, the stems of other shrubs. The stems are round and grooved with bristly spines.

Maybe about 75-100 meters up the arroyo, we came to a low bank composed of shell fossils. Warren explained that it was an oysterbed, with numerous layers of shells, each separated by a layer of pebbles and small stones. All of the arroyos in this area have these exposed oysterbeds. He said that each layer of pebbles/stones probably represented an underwater landslide event that smothered the oysters, after which new oysters would begin anew on top. Near the top of the exposed bank, oysters can no longer be found. The age of the oysterbed is estimated to be around 125,000 years when the sea level was about 6 m higher.

Warren ready to talk about the oysterbed.

Fossil oysterbed.

Approximately one half of the sediments in the oysterbed is comprised of the calcareous tests of rhodoliths. Rhodoliths are "unattached, calcareous nodules composed of benthic marine red algae that resemble coral...[and] they are important for creating habitat for diverse benthic communities." [Wikipedia] These coralline algae deposit calcium carbonate within their cells to form these hard nodules. There are still living rhodolith beds about 2 kilometers offshore.

Approximately one half of the sediments in the oysterbed is comprised of the calcareous tests of rhodoliths. Rhodoliths are "unattached, calcareous nodules composed of benthic marine red algae that resemble coral...[and] they are important for creating habitat for diverse benthic communities." [Wikipedia] These coralline algae deposit calcium carbonate within their cells to form these hard nodules. There are still living rhodolith beds about 2 kilometers offshore.

Warren also talked about an unsolved mystery found in this particular oysterbed: the presence of rounded granite stones in the same layers that smothered the oysterbed layers (salt and pepper color stone pictured at right). Why is this such a mystery? His answer is: 1). the stones apparently are part of an alluvial flow that is found in a bed only about 125,000 years old; and 2). there are no known granites on the peninsula and the nearest diorite deposits (rocks very similar to granite) are located about 250 miles to the northeast in the Cataviña area, much too far away for them to have ever been carried here by alluvial action.

Our final stop of the day was located near the top of one of the limestone bluffs visible from the beach that form Mesa Atravesada (see photo above with caption that begins: "Scrub typical to the ancient seabed...". The area is accessible by a narrow road off of the main road near the inland end of the airstrip. The continues beyond where we stopped (see #4 on map), but was getting too narrow for the all of the vehicles to be able to turn around.

Some of the rocks at the very top of the bluff were darker and of volcanic origin while the limestone beds were located a meter or more below the cap. Warren said that many of the chunks of limestone in the bluffs had drill holes in them created by clams. In Spanish, cacarizo means "pocked" and Punta Cacarizo (Hammerhead Point to gringos), which was right near our first stop of the tour, is a low, flat limestone shelf that is pockmarked with these drill holes. From our lookout, we looked down into a wide valley and plain behind Ensenada de los Muertos that had also been underwater in the distant past.

A limestone bluff on the western edge of Mesa Atravesada.

Huge chunks of the limestone have broken off. Drill holes are visible.

Near the top of the bluffs. The lower crumbly rock is limestone.

Close up of some limestone chunks, which are cream to yellowish.

Megalodon tooth. While this is not a tooth that was found locally, Warren brought it for show-and-tell, since fragments of these ancient shark teeth have been found in the limestone bluffs.

Northeast edge of Mesa Coloradito, where the side road to the limestone bluffs (#4) begins. Johnson (2002) describes this as an andesite ridge (of volcanic origin). Lava outcrops are visible.

The north end of Punta Cacarizo showing its connecting sand spit.

The south end of Punta Cacarizo and spit.

A slab of limestone by the road that is full of fossilized shells.

A closer look at the slab. Click on the photo for an even closer view.

Botany Notes.

There were just too many people on the tour for me to get to spend time on more than a few of the local plants as we walked, but I did take the opportunity to talk about the local plant communities and some of the basic desert adaptations that we had or would see at the upcoming stops. Later, at lunch once the tour was done, some of us discussed having a plant walk with a much smaller group in April, so at the end of the month I headed back out there to do just that. I didn't get many photos during my first trip, so I took advantage of being back in PC to get a few more to add to this issue.

Below are some more images of plants we that we saw either on the tour or the plant walk. The first four photos below are from a dry winter in February and show a number of the shrubs and perennials common to PC and the general Gulf Coast area around Mulegé. Many of the trees and shrubs tend to start blooming in April or May in spite of it being very dry.

Several more images of other areas of Punta Chivato can be seen on the locations page as well as on the gypsiferous soils section of the Mulegé Flora Project.

Galloping Cactus (Stenocereus gummosus) with Casa Rata (Grusonia invicta) in the foreground.

San Marcos Cotton (Gossypium armourianum) is a rare, local endemic shrub, known only from Isla San Marcos (not far from PC) and the Gulf Coast between Santa Rosalia and Mulegé. This is one of two endemic cottons in BCS, the other being G. harknessi which is restricted to mostly coastal areas near Loreto.

Unlike that species, the leaf margins of San Marcos Cotton are all entire and mostly glabrous, rather than stellately pubescent and shallowly 3-lobed. Flowers bracts of G. harknessi are persistent until or after flowering while those of San Marcos cotton fall before flowering. The flowers of both are approx. 3.5-4 cm D.

Espadín (Euphorbia ceroderma) is rare in the Mulegé region where it is found only in the calcium (gypsum)-rich soil in parts of PC. The taxa is more common in the state of Sonora on the other side of the Gulf.Populations are disjunct (fragmented), with various populations along the Pacific coast around San Juanico and the Comondús.

Espadín is a rounded, cespitose shrub with stiff green stems to about 1.75 m H. Pencil like stems are c. 1-1.5 cm D and will turn red, esp. the tips, when stressed. The latex sap can ooze from any of the leaf nodes. Ephemeral leaves are filiform (1-1.5 cm L) and the flowers are c. 3-5 mm D and lack petals but have 5 petalloid glands.

Gulf Tansy-Aster (Xanthisma incisifolium) is a perennial that occurs mostly on islands in the southern Gulf, but can also be found on slopes and dunes along the coast at least as far north as PC to Loreto. This was the largest specimen I´ve seen at PC.

Gulf Tansy-Aster herbage is well adapted to dune life with semi-succulent herbage densely covered in glandular hairs. Flowers are 2.5-3 cm D. A lot of the achenes get stuck to the plant for awhile, perhaps an advantage in a habitat with strong winds and moving sand.

The glandular leaves are sticky and actually stick somewhat to each other such that stems form a dense mass. Flowers have a low profile.

The leaves of Gulf Tansy-Aster are incised, with most of the lobes having a tiny spine at the tip. Sand grains stick easily.

I can't believe how fast the season has passed. Soon I'll be heading back north to the US and hopefully I'll get to see some late Spring botanical action along the way. I'm not sure yet what next month's entry will bring, so until then, Hasta pronto...see you soon.

Debra Valov — Curatorial Volunteer

For a full inventory list of this month's plants (family, latin name and common names in both English and Spanish as well as links to photos from previous posts or my iNaturalist observations), visit this page.

References and Literature Cited

Johnson, Markes E. (2002) Discovering the Geology of Baja California.

Six Hikes on the Southern Gulf Coast. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ.

Rebman, J. P., J. Gibson, and K. Rich, (2016). Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History, No. 45, 15 November 2016. San Diego Natural History Museum, San Diego, CA. Full text available online.

Rebman, J. P and Roberts, N. C. (2012). Baja California Plant Field Guide. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. Descriptions and distribution.

Valov, D. (2020). An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Mulegé, Baja California, Mexico. Madroño 67(3), 115-160, (23 December 2020). https://doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-67.3.115

Wiggins, I. L. (1980). The Flora of Baja California. Stanford University Press. Keys and descriptions.

Our third stop of the day was not very far west from the previous one, but because of some deep ravines between the two and the lack of a direct road, the drive took about 15 minutes. After all the cars had arrived and parked, we all gathered around so I could talk briefly about the plant communities at PC as well as about what we were seeing right where we were standing...which was on an ancient seabed that had secondary gypsum deposits, embuing it with a pale gray color, and that was home to what was currently a lot of very gray, mostly leafless plants.

Our third stop of the day was not very far west from the previous one, but because of some deep ravines between the two and the lack of a direct road, the drive took about 15 minutes. After all the cars had arrived and parked, we all gathered around so I could talk briefly about the plant communities at PC as well as about what we were seeing right where we were standing...which was on an ancient seabed that had secondary gypsum deposits, embuing it with a pale gray color, and that was home to what was currently a lot of very gray, mostly leafless plants.