Mexico's Baja California peninsula is the world’s second longest peninsula. It consists of a number of different ecosystems and harbors a wide variety of plant and animal life, many species which are found no where else on earth in the wild. In this section, you will learn more about the peninsula and the many ways that it's unique resources are being protected.

Mexico's Baja California peninsula is the world’s second longest peninsula. It consists of a number of different ecosystems and harbors a wide variety of plant and animal life, many species which are found no where else on earth in the wild. In this section, you will learn more about the peninsula and the many ways that it's unique resources are being protected.

You'll find links to the class handouts used at ISSI (Intensive Spanish Summer Institute) here and in the ISSI archives. You can also link here to the vocabulary list for this topic or see the spanish translation by clicking on individual red words in the text below.

The Baja California peninsula is 760 miles long and has an area of 89,100 sq. miles. It has almost two thousand miles of coastline and is bound on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the east by the Gulf of California (or Sea of Cortéz), both of which are incredibly rich in marine life. Its geologic history has led to a uniquely varied environment with a wide range of habitats and a high level of biodiversity.

While over 60% of the peninsula’s landmass falls within the Sonoran Desert, there can be found mangrove and dry tropical forests in the south as well as snow-capped mountains with pine forests in the northeast. The Gulf is host to the northernmost coral reef in the America’s, while three shallow Pacific Ocean lagoon systems form refuges and provide nurseries for California gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) at the southern range of their annual migratory path.

A small population of berrendo, or Peninsular Pronghorn Antelope, an endemic subspecies (Antilocapra americana ssp. peninsularis) roams the vast, mostly unpopulated plains of the Vizcaíno Desert Region. The vestiges of yet another protected species, the borrego cimarrón or Peninsular Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis ssp. nelsoni) are now restricted to the steep slopes of the Sierra San Borja, Sierra San Francisco, the Las Tres Vírgenes volcano complex, the Sierra de Guadalupe, and the Sierra de la Giganta.

A small population of berrendo, or Peninsular Pronghorn Antelope, an endemic subspecies (Antilocapra americana ssp. peninsularis) roams the vast, mostly unpopulated plains of the Vizcaíno Desert Region. The vestiges of yet another protected species, the borrego cimarrón or Peninsular Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis ssp. nelsoni) are now restricted to the steep slopes of the Sierra San Borja, Sierra San Francisco, the Las Tres Vírgenes volcano complex, the Sierra de Guadalupe, and the Sierra de la Giganta.

Few remnant populations remain of the original native (indigenous) cultures (Kumiai, Paipai, Cocopa and Kiliwa in northern Baja California and the Cochimí, Guaycura and Pericu of the southern regions). However, descendents of these tribes are currently showing a renewed interest in reclaiming their indigenous roots and cultures. The indelible marks of the peninsula’s prehistoric inhabitants are still evident in the hundreds of rock art sites dispersed throughout the peninsula. Baja’s rock art reached its apex in the central region, where cave paintings in the “Great Mural” style (el estilo de Gran Mural), estimated to be perhaps at least 7,500 years old, adorn isolated caverns and rock overhangs of the sierras.

For the most part, the peninsula is a rugged, uninhabited place, with little water, and with native species of flora and fauna that are well adapted to their present environment. It is the isolation and rugged wildness of Baja that has attracted so many visitors since the 1800’s, many of whom were seeking monetary, scientific and spiritual riches. Others came looking for adventure or to settle Mexico’s frontier. Ironically it is the peninsula’s pristine nature and isolation that has both lured so many and simultaneously led to the growing exploitation of its resources and its environmental degradation.

For the most part, the peninsula is a rugged, uninhabited place, with little water, and with native species of flora and fauna that are well adapted to their present environment. It is the isolation and rugged wildness of Baja that has attracted so many visitors since the 1800’s, many of whom were seeking monetary, scientific and spiritual riches. Others came looking for adventure or to settle Mexico’s frontier. Ironically it is the peninsula’s pristine nature and isolation that has both lured so many and simultaneously led to the growing exploitation of its resources and its environmental degradation.

Protected Areas & Species

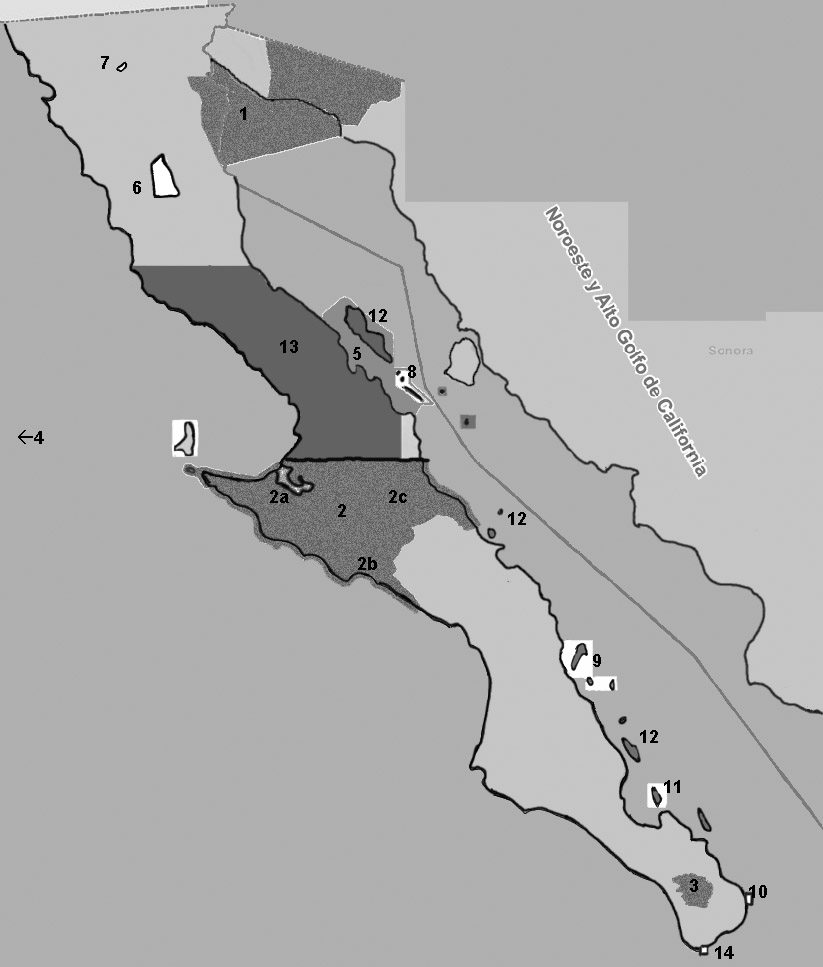

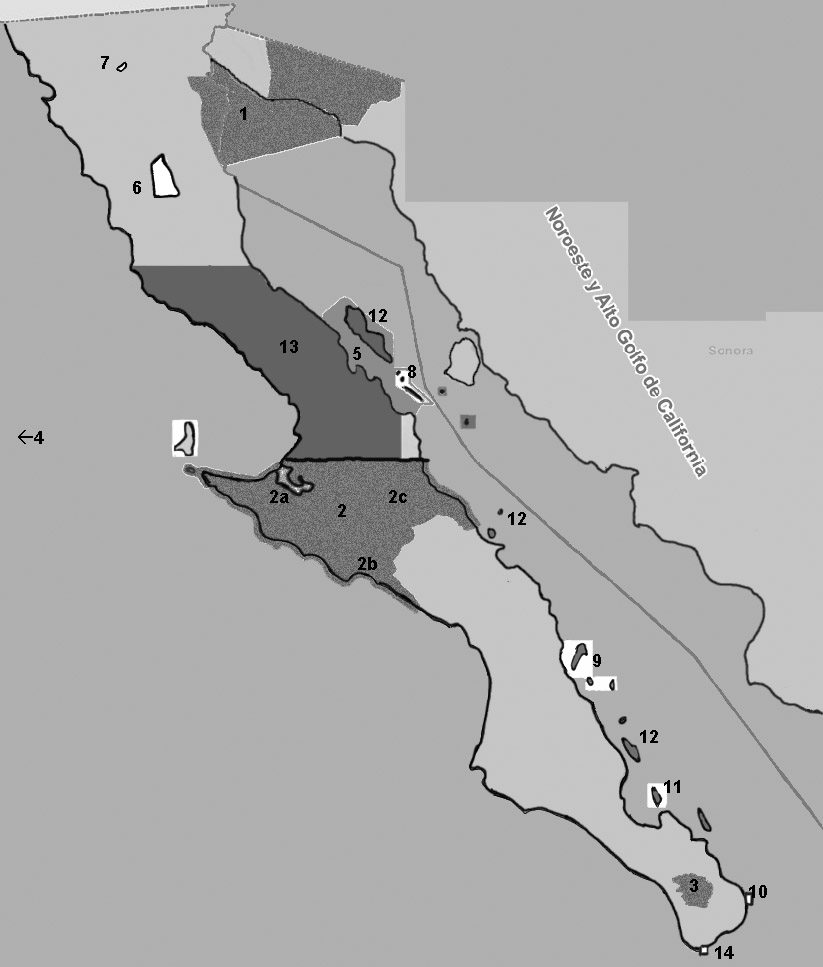

The Baja Peninsula is host to a wide range of officially established protected natural areas, including four terrestrial and two marine National Parks, four Protected Natural Areas, various Wildlife Sanctuaries, and five Biosphere Reserves, of which the Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve is the largest protected area in Latin America. The Vizcaíno is also recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site for its cave paintings and whale, bighorn sheep, and pronghorn sanctuaries. A new Biosphere Reserve for the Sierras de la Giganta and Guadalupe was recently declared on June 27, 2014, but the process has yet to be completed. Read more on this news here. Visit the CONABIO site for full listings in Baja California and Mexico.

Biosphere Reserves

- Alto Golfo de California y Delta del Río Colorado, Sonora/BC

- Vizcaíno, BCS

- Ojo de Liebre Complex

- Laguna San Ignacio

- Sierra San Francisco

- Sierra de la Laguna, BCS

- Isla Guadalupe, BCN

- Reserva de la Biósfera Bahía de los Ángeles, Canales de Ballenas y de Salsipuedes

|

National Parks

- San Pedro Mártir, BC

- Constitución de 1857, BC

- Archipiélago de San Lorenzo, BC

- Bahía de Loreto, BCS

- Bahía de Cabo Pulmo, BCS

- Archipiélago de Espíritu Santo

|

Protected Natural Areas (ANP)

- Islas del Golfo de California,BC/BCS/Sonora

- Valle de los Cirios

- Las Cascadas de Arena& el Estero San José del Cabo

- Balandra

|

In addition to pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, and gray whales, there are a number of other threatened species on the peninsula that are federally protected: five of the world’s seven species of sea turtles either nest on peninsular beaches or feed in its waters; and a number of other whale species (e.g., Blue, Humpback, Finn) call the region home. Plants species and their habitats are also protected: over 100 species of cacti, about 80% of them endemic and found nowhere else on earth, are under federal protection as are mangrove forests and portions of the arid tropical forest of the Cape Region.

Environmental protection has a long history in Mexico and conservation on the peninsula was well underway by the 1970’s with the establishment of the gray whale sanctuaries on the Pacific Coast.

Mexico’s environmental laws, and more specifically the General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection first passed in 1988 (and with several subsequent, significant amendments), are among the world’s strongest and most forward-looking. However, like all laws, their effectiveness depends on the government’s willingness and ability to apply and enforce the statutes and the influence of the business sector and local governments in bypassing or thwarting them.

A wide range of local and international non-profit organization (NGOs) have formed to address conservation issues and they have continued to be instrumental in conserving the wild peninsula and its flora and fauna. At all levels (from school children to adults, and from small, informal, grassroots groups to service providers to well-funded binational environmental groups) their active participation has been vital in identifying problems and seeking solutions that benefit both the environment and the economic interests of the communities involved. In Loreto in May 2011, over 300 scientists, NGO leaders and government officials gathered at the first Conservation Science Symposium where they discussed how science could be applied to the conservation and management of natural resources on the Baja California peninsula and throughout the Gulf of California.

A wide range of local and international non-profit organization (NGOs) have formed to address conservation issues and they have continued to be instrumental in conserving the wild peninsula and its flora and fauna. At all levels (from school children to adults, and from small, informal, grassroots groups to service providers to well-funded binational environmental groups) their active participation has been vital in identifying problems and seeking solutions that benefit both the environment and the economic interests of the communities involved. In Loreto in May 2011, over 300 scientists, NGO leaders and government officials gathered at the first Conservation Science Symposium where they discussed how science could be applied to the conservation and management of natural resources on the Baja California peninsula and throughout the Gulf of California.

The intersection of governmental agencies with private sector businesses and local citizens groups has led to: a capture-captive breeding-release program aimed at increasing the number of berrendo; a stewardship-hunting program that maintains a healthy population of bighorn sheep; numerous hatcheries that annually release tens of thousands of baby sea turtles; the ongoing protection of the whale nurseries amidst pressures for industrialization of these areas; and a general overall increase in ecotourism. While problems do exist throughout the peninsula, such as a lack of sufficient governmental funding aimed at enforcement and some programs with questionable success, the overall trend is a positive one as all sectors come together to find creative solutions.

The intersection of governmental agencies with private sector businesses and local citizens groups has led to: a capture-captive breeding-release program aimed at increasing the number of berrendo; a stewardship-hunting program that maintains a healthy population of bighorn sheep; numerous hatcheries that annually release tens of thousands of baby sea turtles; the ongoing protection of the whale nurseries amidst pressures for industrialization of these areas; and a general overall increase in ecotourism. While problems do exist throughout the peninsula, such as a lack of sufficient governmental funding aimed at enforcement and some programs with questionable success, the overall trend is a positive one as all sectors come together to find creative solutions.

File Downloads

Bajar documentos

- Conserving the Peninsula Class Handout (ISSI)

- Conserving the Peninsula Presentation (ISSI)

- Presentación de conservar la peninsula (ISSI)

- Vocabulary list (ISSI)

- Artículos sobre el medioambiente I (del periódico El Sudcaliforniano) PDF | RTF (doc)

- Artículos sobre el medioambiente II (del periódico El Sudcaliforniano) PDF | RTF (doc)

- La deforestación en México PDF | RTF (doc)

- Presentación sobre el Berrendo Peninsular

- Informe del Berrendo Peninsular (SEMARNAT, 2009)

Links

Enlaces

Governmental Agencies / Entidades Gubernamentales

CONABIO Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity)—responsible for managing protected areas.

See also: Biodiversity portal

CONANP Comisión Nacional de las Áreas Naturales Protegidas

See also: el material didáctico en español

PROFEPA Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente (Federal Prosecutor for the Protection of the Environment)—Mexico’s judicial branch of the environmental protection agency.

SEMARNAT Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Secretariat of the Environment and Natural Resources)—Mexico’s legislative branch of the environmental protection agency.

See also: SEMARNAT digital library of resources

Environmental NGO’s/ONG’s Ecologistas (en defensa del medioambiente)

Colorado River Project. (Project to return flow to the river´s delta. Watch this video released July 2014 and narrated by Robert Redford.

EcoAlianza (Loreto, BCS) (su sitio en español). Also on Facebook.

Grupo Tortuguero (network of turtle activists, NGO’s, ecotourism)

Grupo Tortuguero de Todos Santos, A.C. (hatchery in Todos Santos). Or visit their Facebook page for current events.

Proesteros (Wetland conservation in northern BC)

Sociedad de Historia Natural Niparajá, A.C. (NGO in La Paz, BCS)

TerraPeninsular (land purchase/conservation in northern BC). See their site in Spanish or like their Facebook page.

Tortugueros Las Playitas (adopt a baby sea turtle, volunteer). Visit their Facebook page.

WildCoast (Costa Salvaje is their name & site in Spanish) (peninsula-wide activities, media blitzes)

Ecotourism Providers / Prestadores de Servicios Ecoturísticos

Baja Discovery (whale watching)

Hotel Villas Mar y Arena (Puerto San Carlos, BCS; hotel, restaurant, whale watching tours, group transportation). They are also on Facebook.

Kuyima (whales, birds, turtles, Vizcaíno, cave paintings, kayaking, camping). Visit them on Facebook.

Mario's Tours (Whale watching in Guerrero Negro, BCS). Also on Facebook

Pachico Ecotours (whale watching). Like their Facebook page.

Environmental Education/la Educación Medioambiental

Baja California Field Studies Program, Glendale Community College (short field courses at station at Bahía de los Ángeles; check out their photo page for spectacular shots of the area and class activities) On Facebook

Project Aware (a variety of education projects and issues dealing with ocean conservation, including responsible diving practices)

PROBEA (bilingual educational materials)

Ocean Oasis (Baja natural history information—teacher’s manual english/spanish, DVD)

Protected Areas / Las Áreas Protegidas

Archipiélago de Espíritu Santo

Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Islas del Golfo de California

Amigos de Cabo Pulmo (local NGO). Site in English.

Parque Nacional Zona Marina del Archipiélago de San Lorenzo

Reserva de la Biósfera Bahía de los Ángeles, Canales de Ballenas y de Salsipuedes

Vizcaíno Reserve

See: a description of park (pdf)

Ve: la descripción del parque (pdf)

Parque Nacional Bahía de Loreto (Facebook group)

Sierra de la Laguna Reserve

Sierra de la Laguna (Facebook group)

Amenaza minera: Niega permiso a la minera Paradones Amarillos

Mining Threats in the Cape Region

Defiende la Sierra (Citizens and NGOs united to defend the Cape Region against mining threats)

Wild Sea: EcoWars and Surf Stories from the Coast of California Book by Serge Dedina (2011)

Media Sources

Melóncoyote (Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness - quarterly environmental journal with Spanish and English on-line versions)

More links to articles and videos can be found in the ISSI archive

Mexico's Baja California peninsula is the world’s second longest peninsula. It consists of a number of different ecosystems and harbors a wide variety of plant and animal life, many species which are found no where else on earth in the wild. In this section, you will learn more about the peninsula and the many ways that it's unique resources are being protected.

Mexico's Baja California peninsula is the world’s second longest peninsula. It consists of a number of different ecosystems and harbors a wide variety of plant and animal life, many species which are found no where else on earth in the wild. In this section, you will learn more about the peninsula and the many ways that it's unique resources are being protected.  A small population of berrendo, or Peninsular Pronghorn Antelope, an endemic subspecies (Antilocapra americana ssp. peninsularis) roams the vast, mostly unpopulated plains of the Vizcaíno Desert Region. The vestiges of yet another protected species, the borrego cimarrón or Peninsular Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis ssp. nelsoni) are now restricted to the steep slopes of the Sierra San Borja, Sierra San Francisco, the Las Tres Vírgenes volcano complex, the Sierra de Guadalupe, and the Sierra de la Giganta.

A small population of berrendo, or Peninsular Pronghorn Antelope, an endemic subspecies (Antilocapra americana ssp. peninsularis) roams the vast, mostly unpopulated plains of the Vizcaíno Desert Region. The vestiges of yet another protected species, the borrego cimarrón or Peninsular Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis ssp. nelsoni) are now restricted to the steep slopes of the Sierra San Borja, Sierra San Francisco, the Las Tres Vírgenes volcano complex, the Sierra de Guadalupe, and the Sierra de la Giganta. For the most part, the peninsula is a rugged, uninhabited place, with little water, and with native species of flora and fauna that are well adapted to their present environment. It is the isolation and rugged wildness of Baja that has attracted so many visitors since the 1800’s, many of whom were seeking monetary, scientific and spiritual riches. Others came looking for adventure or to settle Mexico’s frontier. Ironically it is the peninsula’s pristine nature and isolation that has both lured so many and simultaneously led to the growing exploitation of its resources and its environmental degradation.

For the most part, the peninsula is a rugged, uninhabited place, with little water, and with native species of flora and fauna that are well adapted to their present environment. It is the isolation and rugged wildness of Baja that has attracted so many visitors since the 1800’s, many of whom were seeking monetary, scientific and spiritual riches. Others came looking for adventure or to settle Mexico’s frontier. Ironically it is the peninsula’s pristine nature and isolation that has both lured so many and simultaneously led to the growing exploitation of its resources and its environmental degradation.

The intersection of governmental agencies with private sector businesses and local

The intersection of governmental agencies with private sector businesses and local